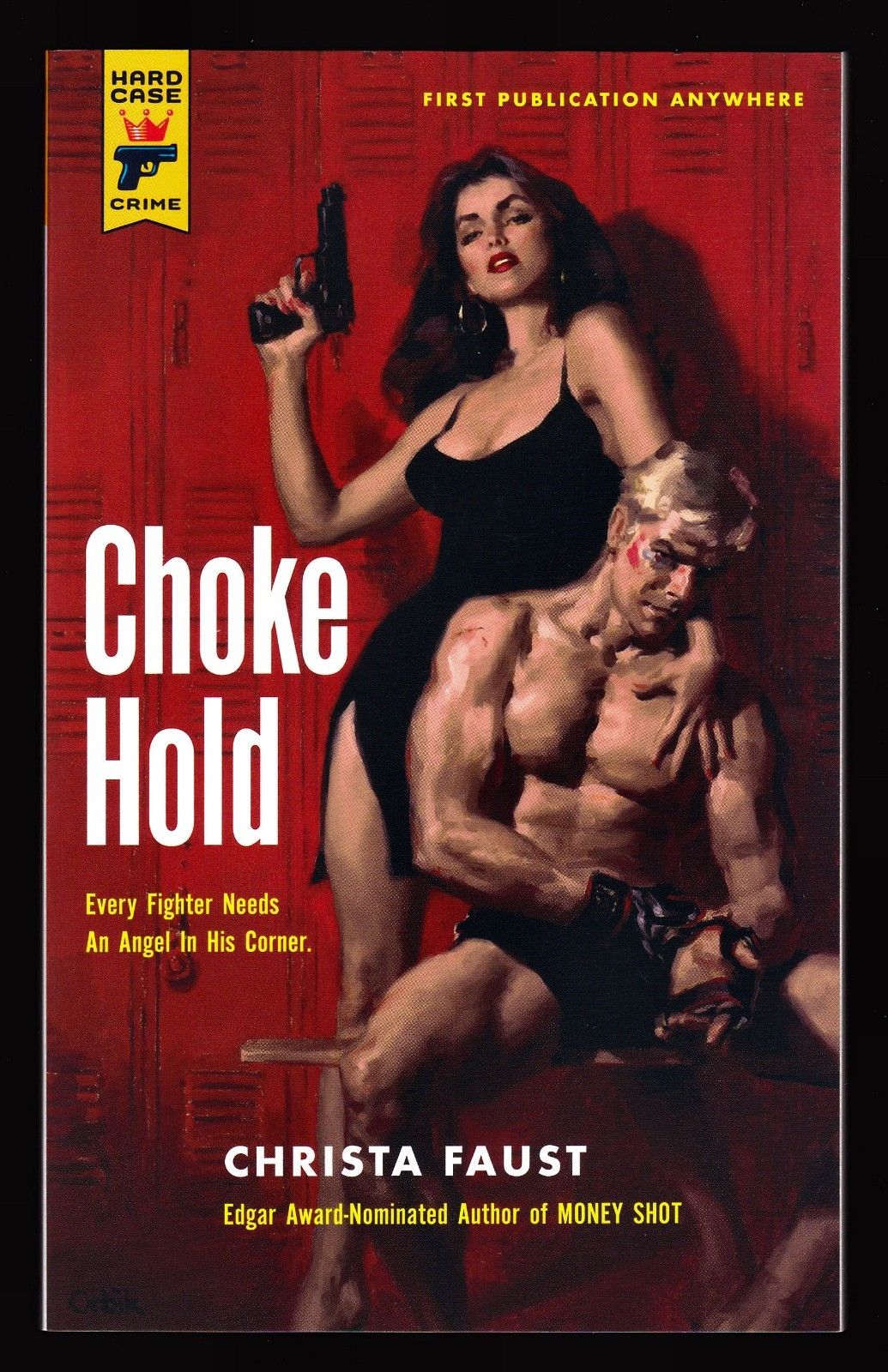

Choke Hold is the 2011 sequel to Christa Faust’s Money Shot. It offers the first-person narrative of former porn actress Angel Dare as she tries to save the mixed martial artist son of a former lover from being murdered by gangsters. Faust offers a fast-paced, gritty, action-packed narrative that offers a more critical, more aware view of violence and rape than you often find in similar noir novels. This is pulp, through and through, but it’s smart and well-written.

I picked up this novel in part because I was struck by Faust’s vivid, deftly-used descriptions in Money Shot, and I wanted to see if she employed the same techniques here. The opening chapter takes place in a diner where Dare is working under an assumed name. We get nearly no details about the diner itself; the descriptive focus is entirely on the people Dare encounters:

I looked over at the kid Vic was talking about. He was barely eighteen. Broken nose but still way too handsome for his own good. Intense hazel eyes and dark hair buzzed down to the scarred scalp. Lean, athletic build under an expensive white t-shirt printed with trendy rococo designs, silver skulls and wings. His long, sinewy arms were already sleeved in unimaginative tattoos. There was a red and black motorcycle jacket slung over the back of the booth and a brain-bucket style helmet on the table beside him. He was trying a little too hard and wore bad-ass like a brand new pair of boots that hadn’t quite broken in yet. He’d ordered nothing but black coffee and flirted with me every time I came around to fill his cup … like some hot young gun who thinks he doesn’t need Viagra for his first scene.

Glossing over the diner works, because to Dare it’s a boring, familiar location; she wouldn’t give it much thought, and further describing the location would just slow things down. But Vic’s son is new to her. We know from the description of his broken nose and scarred scalp that he’s a fighter, and probably in training because he’s ordering his coffee black. And we get a good sense of Dare — her age, her experiences, her mindset — from the language choices in the narration. She finds his trendy tattoos unimaginative. He’s a just kid to her, not a potentially dangerous man. His helmet is a brain bucket. And we know without being told outright that she used to work in porn.

Later, we get brief, selective descriptions of new locales:

Nine Iron Drive was a long swath of stillborn potential, plot after empty plot waiting for homes that would never be built. Down near the dead end of the street stood a single orphan house.

Though these two sentences still lack specific detail, “stillborn potential” is a nicely dark, compact way of describing the kind of failed land developments we’ve all seen. And the orphan house echoes the stillbirth imagery. Both convey the anxiety that the childless Dare is feeling for Vic’s son; she’s wrestling with unfamiliar emotions of feeling responsible for him now that Vic’s been murdered, and also she’s uncomfortably aware that under slightly different circumstances he could have been her own son.

Faust’s description is a good study for writers of commercial fiction who are looking for ways to keep their narratives tight, focused, and fast-moving while retaining intelligence and style.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.